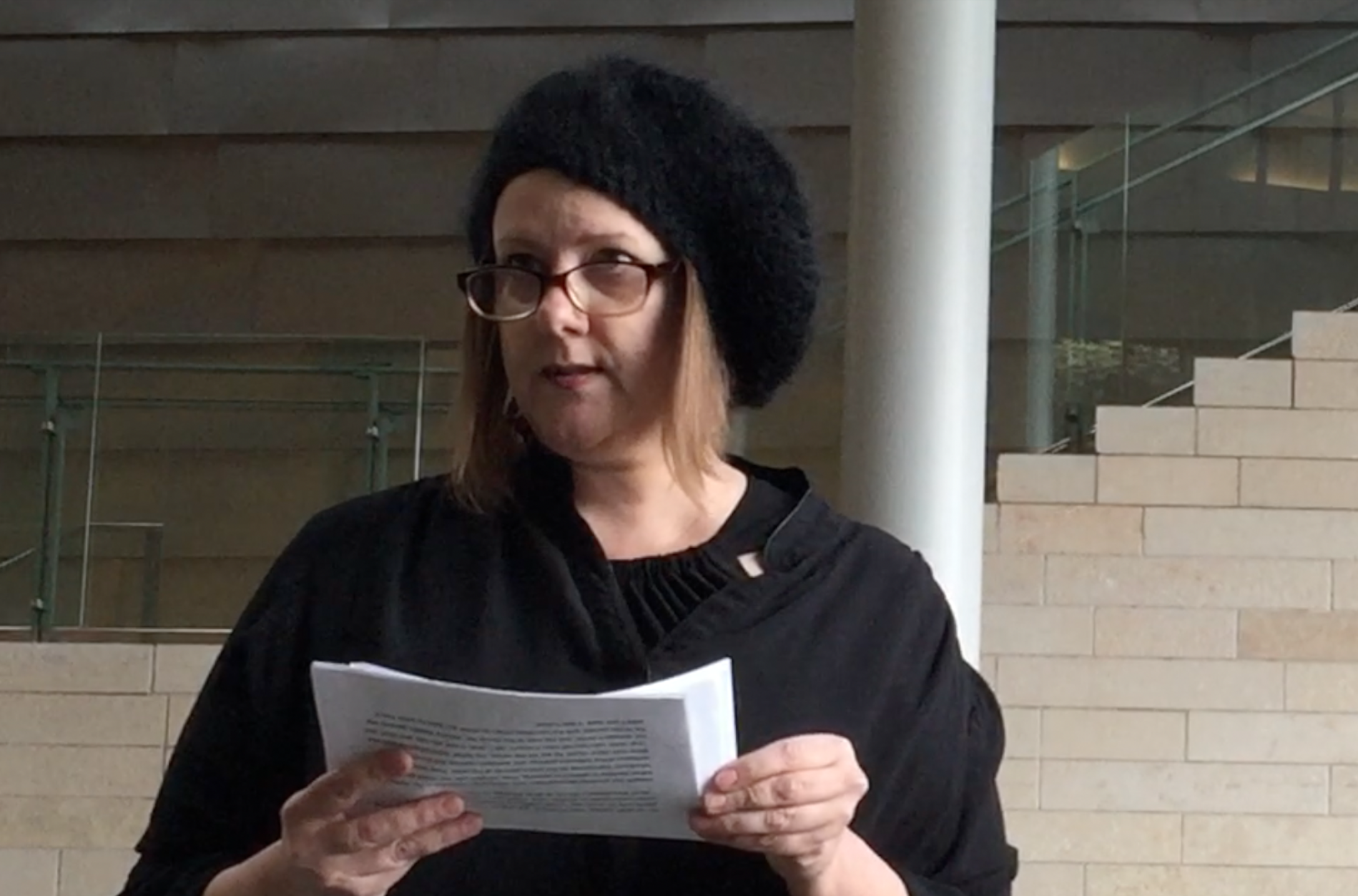

On Friday, February 27, in conjunction with the exhibition The Incredible Intensity of Just Being Human, Brian Moss, MA, LMFT and I gave a talk at Seattle City Hall about some fairly incendiary topics. This is my Opening Statement:

I’m an artist, curator, web developer, and activist. I did my first show on child abuse over 25 years ago. It was a little solo exhibition in conjunction with a performance piece by another artist. There were certain incidences of abuse that I never dissociated, that is, I did not develop amnesia for them.

Despite our growing estrangement, and not having invited them, my mother and father decided to attend the opening. They mingled with the crowd and introduced themselves as the proud parents of the artist. They looked a little confused at the sideways glances and awkward silences this provoked. The show was about incest. As we left the venue, my father approached me and said, “Just make sure you tell them it wasn’t me.” Well, it was you dad, and mom, and our extended family, and the men at the corner bar, and the wealthy general and his house guests, and the countless others to whom you sold my body. And it wasn’t just rape, it was torture.

I’m going to say something now that gave Kate a little start the first time I said it. I don’t have a mental illness. This exhibition was organized to help combat stigma. I contend that the source of stigma is not so much the fear of encountering anti-social behavior or odd symptoms, it’s the fear of what they represent.

Depending on the study, between 89 and 98% of people receiving mental health care services have a history of trauma. The recent, and massive, Adverse Childhood Experiences study determined that a history of child abuse significantly increases the probability of a range of chronic and serious health issues in adulthood. Other researchers are discovering that psychotic delusions have meaning and can be decoded. They are attempts to both communicate and defensively contain, through non-arbitrary systems of symbols, the pain of a primal wound.

I don’t think that mental illness is the central problem, I think violence is the problem. A large majority of the people who are diagnosed with mental illnesses represent walking, talking reminders of our failure to place stigma where it truly belongs, on the behavior of human beings who resort to violence as a strategy of control, and the failure of our culture to address this all too common human frailty. It is easier to make into scapegoats and pariahs the victims of violence, to label our normal, adaptive responses to trauma as illnesses and disorders. It is easier to create this great distraction rather than to confront the fear that some of the humans on whom we depend in society are quite dangerous.

To quote a friend of mine, Jeanne Sarson, “When people talk about Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, we say no, we disagree, you might have traumatic stress responses, but we are unwilling to say you have a disorder. What are people expecting of someone who withstands torture, to come out of it laughing? That’s the insanity of calling these responses a disorder.”

So today I will say, I have Dissociative Identity Response. It is not a disorder. It is not a chemical imbalance, or a genetic defect. It is not a bizarre set of symptoms to be fascinated with or sensationalized in the media. On the contrary, if I hadn’t been able to dissociate, I would not be standing here speaking to you. It saved my life. Where all eyes should be focused is on the violence that caused it. That violence, and my condition were utterly and completely preventable.

However, my case is a bit complicated.

All humans have some ability to dissociate. To dissociate is to remove oneself mentally from the immediacy of an experience, to not stay fully attentive to what is happening in the moment. If there is no escape from ongoing violence, one may mentally remove oneself from the experience to the degree that there is amnesia for the experience later.

My family was part of a network of people who trafficked children. As you might imagine, it would be highly beneficial for child traffickers if their victims couldn’t remember what had happened to them. If you can’t remember, you can’t tell. So from an early age, my natural tendency to dissociate from the violence was encouraged, but it got worse than that. The trafficking network had connections with personnel running Cold War initiated human experimentation programs. Around the age of 4, I was tested and inducted as a subject. My family was rewarded. They were told that they were doing their patriotic duty, and that I would be set for life. I have not been set. In one way or another, my entire life, I have been working to recover from what was done to me.

Throughout my childhood, 4 to 5 times per year, I was sent to hospitals and military bases where I was subjected to torture. The torture consisted of food, water, sleep, and sensory deprivation, confinement, mock drowning, sexual assault, electric shock, drugging, and sensorial trickery using movies, sound, mirrors, medical equipment, and other apparatuses so diabolical, a Hollywood screenwriter couldn’t imagine them. The torture was used to force me to dissociate, and then as aversive conditioning if I did not dissociate in the correct way. If you can imagine the impact of using torture-based aversive conditioning on a growing mind, the behavior and thought patterns have been very difficult to undo. It’s the weight of the grief however, that cannot be undone. I feel my soul is not wide or tall or deep enough to ever encircle it, and so I will always be divided, …and, I make art.

Comments are closed.